A branch of my family has lived in Attica, NY, for 80 years. Less than a mile from the small, bucolic upstate town is the maximum-security prison that’s (in)famous for an uprising where 32 prisoners and 11 hostages were killed during the violent retaking in September 1971.

My maternal great-grandfather was a plumbing instructor at the prison in the late 1940s, after moving to Attica when he retired. My mother and her siblings remember that the town had an ice cream store and a movie theater and that their grandparents’ house—at 19 Walnut Street—had an outdoor pump with refreshing icy cold water. She remembers that her dad avoided driving past the prison on the way in to town.

Given this personal history, I was interested to read Blood in the Water: The Attica Prison Uprising of 1971 and Its Legacy, a 2016 Pulitzer-prize winning book on the prison uprising by Heather Ann Thompson. Growing up, I remember hearing the event referred to as a “riot,” so I found the difference in terminology particularly interesting.

The uprising stemmed from the inhumane conditions at the prison, which was overcrowded with mostly Black and Puerto Rican prisoners, some of whom were incarcerated for issues as minor as breaking parole after a teenage joy ride. Others were hardened criminals and/or inmates who had participated in earlier uprisings in other prisons. The inmates suffered from inadequate and poor food, minimal exercise, frequent isolation, brutal and indifferent doctors, and daily mistreatment by racist corrections officers, just to name a few grievances.

During the hot summer of 1971, the commissioner of prisons failed for months to respond to the inmate’s letter asking him to address conditions, and after an incident where two inmates “disappeared” following an altercation with guards, tensions were high. When some of the inmates realized they were trapped in a tunnel leaving the mess hall and were not going to the yard for exercise as was usual, and faced with the head guard responsible for the disappearances, they panicked, fatally injuring a guard and taking 42 staff hostages.

The inmates immediately elected a diverse group of leaders, established a security detail for the hostages, enforced their own rules, and stocked and staffed a medical station. They then asked for the prison authorities to bring in a group of outside negotiators.

During three days of negotiations, the authorities agreed to meet many of the prisoner’s demands for better treatment. They also laid plans to retake the prison by an overwhelming force, arming NYS troopers with weapons outlawed by the Geneva Conventions and (illegally) failing to track who was receiving them. When Governor Nelson Rockefeller gave the OK, officials blasted the inmates and hostages with immobilizing tear gas and followed it up with a barrage of bullets. Ill-prepared state troopers and guards killed 10 of the hostages and 32 prisoners.

“With the exception of Indian massacres in the late 19th century, the state police assault which ended the four-day prison uprising was the bloodiest one-day encounter between Americans since the Civil War.”—McKay Commission Report

Coverups, deliberate sabotage of the many investigations into the uprising, and threatening of coroners and undertakers began immediately. “Repeat a lie often enough and it becomes the truth,” is an idea attributed to Hitler’s propaganda minister, Joseph Goebbels. During the uprising, officials immediately began feeding lies to the journalists covering the event. They made up stories about prisoner abuse of hostages and claimed these were new types of dangerous “radical, militant prisoners.” In truth, the inmates had gone out of their way to protect the hostages, providing mattresses and blankets, medical care and food. In a few cases, the inmates literally took bullets for them during the retaking. None of the hostages were killed by prisoners.

Decades-long lawsuits recounted the horrors inmates suffered at the hands of vengeful corrections officers, both in the immediate aftermath of the retaking, when they were beaten and denied care for their wounds, and in the ensuing months when they were subjected to physical and mental torture.

But, although reporters tried to walk back the horror stories when the truth came out, it was too late. Attica was used to justify some prison reforms (many short-lived), but also a massive backlash that resulted in harsh “tough on crime” laws and punishments that directly led to our current overcrowded conditions and the disproportionate incarceration of Black and brown men.

And Attica itself is now worse than ever.

History Today

“Federal judge orders minority-business agency opened to all races,” by Julian Mark and Taylor Telford. This March 6, 2024, Washington Post article notes how programs originally designed to right historic inequalities has been turned on its head by the ruling that an assumption that minorities are disadvantaged is unconstitutional. Tennessee immediately struck down a provision of the Small Business Administration, forcing the SBA to overhaul it. Of course, the argument fails to consider historical context. Read the article (and see below for a related story).

What I’m Reading

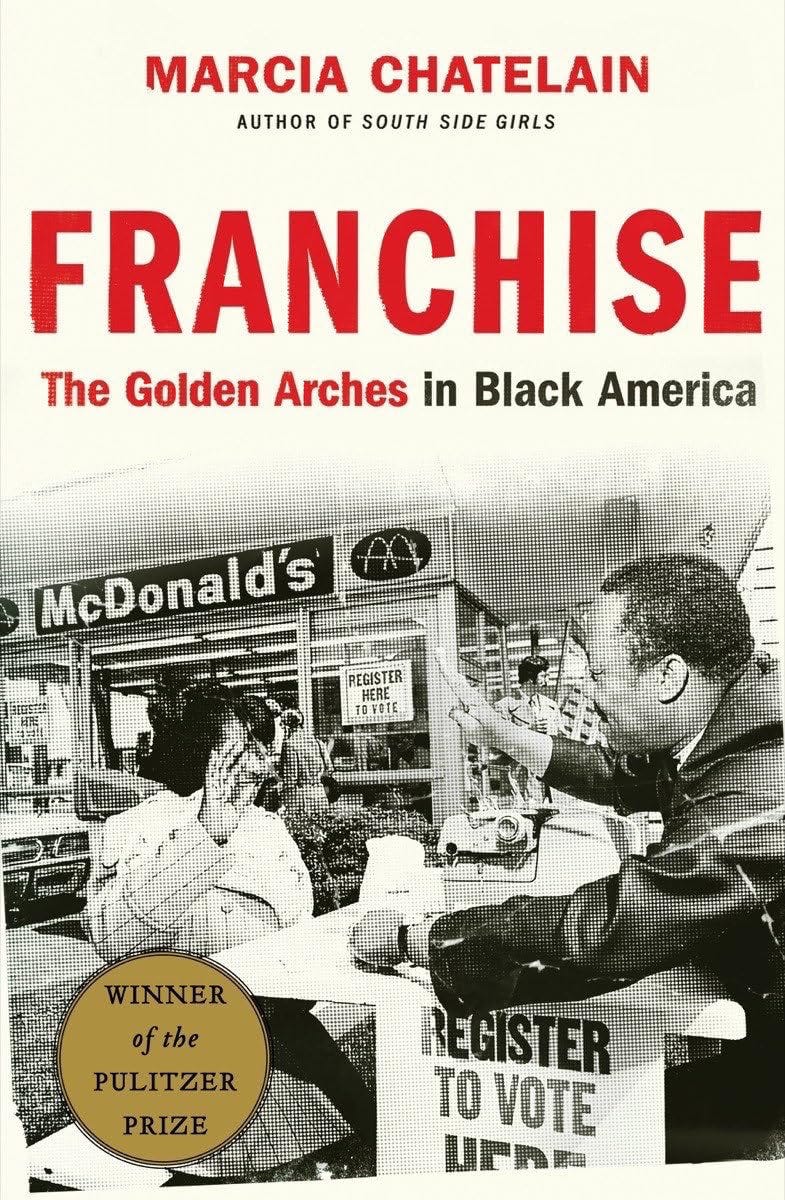

Marcia Chatelain’s thoughtful, well-researched book Franchise: The Golden Arches in Black America (2020), argues that we must look beyond how fast food has contributed to the health problems of Blacks in urban areas and explore the history of the food infrastructure in those communities. She explains that Black ownership of fast-food franchises like McDonald’s was initially sought in the 1960s and ‘70s by civil rights leaders—including Martin Luther King, Jr.—who believed that Black capitalism would further economic justice. The federal government offered special Small Business Administration loans (see above story) to franchisees in the hopes that Black ownership would revitalize neighborhoods hit by economic decline and contain Black unrest. Definitely worth a read.

Incidentally, Black and Puerto Rican Attica prisoners were assigned the most menial tasks in the prison and paid even less than the pennies an hour that the white prisoners received for their labor.

Book News

Nothing new to report. No surprise, I’ve discovered that sales are strongly reliant on advertising and person-to-person marketing. I have not had time (or $) for the first, and my introverted nature rebels at the second.

Here’s how to order Folly Park on Amazon.

Origin Stories

Wind Family, 1939. Anthony G. Wind, Jr. (1907-1987), is standing second from left in the back row. The next adult to the left is my maternal grandfather, Edwin. My mother has always believed that her Uncle Tony worked as a guard at Attica prison. But, in a family tree my sister created in the 1980s, he’s listed as a “plumber.” My sister got that information from my grandmother, so it is likely true. Tony may well have worked at the prison as a plumber given that a dozen years later his father was teaching plumbing there—perhaps his son got him the retirement gig.

As a child, my mom no doubt heard that Tony worked at the prison. Considering that she didn’t like him and believed he was “hard on” his seven children, she may have assumed that meant he was a prison guard—a profession that had the reputation of being violent and dangerous, particularly at Attica.

Wow! I had no idea. It's interesting how our understanding of history gets clearer with time and a new perspective.