President Biden recently announced a new plan to forgive $10,000 of federal student loan debt for each borrower. For those concerned about the disproportionate share of debt held by people of color, particularly Black women, who owe the most, this was welcome news and a matter of racial justice. Black students have less generational wealth to draw on than White students to pay the bills for higher education.

Criticisms of the debt forgiveness plan are many, but some seem strikingly familiar. That it’s too expensive, an example of big government overreach, and will encourage people to be lazy were arguments used 150 years ago by President Andrew Johnson when he rejected plans to aid the newly emancipated slaves.

Historian Eric Foner’s classic work, A Short History of Reconstruction (1990), delves deeply into the time immediately following the Civil War, when many of the conditions that created today’s wealth gap were formed. It’s a complicated story, but by the time Reconstruction ended in 1877, Black people’s status as an underclass had been firmly established.

When the Civil War ended, emancipated slaves and many Union supporters believed that it was only fair they should receive portions of the land they had labored on, unpaid, for generations. Congress authorized the Freedmen’s Bureau to divide abandoned and confiscated Southern lands into 40-acre plots. This redistribution would have weakened the power of the plantation class and provided the former slaves with a means to earn their own livings. However, Johnson ensured it never happened. In areas where the process had already begun, Black families were displaced and the land was returned to its former owners.

Former Confederates worked to restore as much of the slave system as they could. Many Northerners, even those who advocated for the freedmen, assumed the easiest way to restore the South’s economy and transition to a system of free labor was to keep the ex-slaves on the plantations but pay them wages. To ensure that this would happen, Whites refused to rent or sell land to Blacks. In urban areas, only low-wage menial labor was available and Black families were segregated into squalid shantytowns.

States passed Black Codes that required ex-slaves to sign restrictive labor contracts with severe punishments for breaking them, including involuntary plantation labor. Apprenticeship laws required black minors to work for planters without pay. Men, women, and children were whipped, beaten, and hung for “insolence” or “insubordination” as defined by the Codes and interpreted by Whites. Black homes and communities were burned and destroyed. Foner says:

“Freedmen were assaulted and murdered for attempting to leave plantations, disputing contract settlements, not laboring in the manner desired by their employers, attempting to buy or rent land, and resisting whippings. . . . Charges of “indolence” were often directed not against blacks unwilling to work, but at those who preferred to labor for themselves.” (pgs. 53, 60)

Whites also joined together to fix wages at low rates, evicted Black laborers without pay, and refused to give ex-slaves their share of the crop. The freedmen had no recourse with all-White police and judicial systems. They were barred from receiving poor relief and using parks and schools, despite paying taxes to support public services.

Yet, despite the perpetual threat of violence and the difficulties of meeting their basic needs under these conditions, emancipated slaves spent their hard-earned money and limited time avidly pursuing education. Outlawed during slavery (90% of Blacks were illiterate when the Civil War began), education was seen as central to the meaning of freedom. Children and adults flocked to the schools set up in churches, basements, warehouses, and homes. In New Orleans and Savannah, emancipated slaves studied on the sites of former slave markets.

Forgiving student debt is the least we can do.

History Today

Student Debt Cancellation Isn’t Regressive, It’s Anti-Racist

This article explores the details of how the legacy of slavery and the Reconstruction era were extended into the 20th century and contributed to White families amassing ten times as much wealth as Black families. An interesting note is that some New Deal policies that lifted countless White Americans out of poverty excluded Black Americans. The Social Security and National Labor Relations Acts of 1935, for example, made an exception for agricultural and domestic workers, effectively excluding Blacks from their benefits since many worked in those jobs. FDR had made compromises with Southern Democrats to get the programs passed in Congress.

What I’m Reading

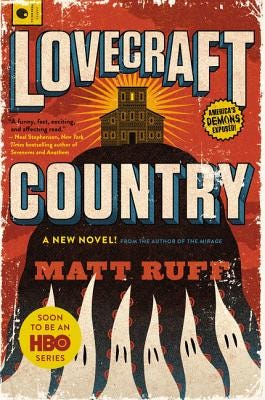

I thoroughly enjoyed this book. Lovecraft Country, by Matt Ruff, satirizes science fiction tropes that traditionally featured only White protagonists. In 1950s America, his cast of Black characters battle a centuries-old order of wizards, time travel to other planets, contend with the effects of magic elixirs, make common cause with ghosts, and deal with nightmares come to life. From 12-year-old Horace to 50s-something Montrose, they are smart, savvy, and capable. Why wouldn’t they be? The horrors and weirdnesses they encounter aren’t much different then navigating a pre-Civil Rights landscape.

Book News

There’s only one month to go until Folly Park releases on November 15th! I’ve been knocking on virtual doors to ask online book reviewers and bloggers to read and review the book. Why? Because, no matter how much we love local bookstores, Amazon is where most people buy books. The more reviews you have, the more likely it is that Amazon’s algorithms will rank your book higher and the more readers will see it.

Sobering fact . . . the average book sells only 500 copies.

Origin Stories

Edwin Robert Wind (1944) and 126 Hendricks Boulevard, Eggertsville, New York (1945). Both of my grandfathers—neither of whom went to college—were able to provide well for their families. My maternal grandfather (above left), opened a chain of dry cleaning stores and was partially retired and spending a lot of time golfing at a second home in Florida even before the youngest of his six children had left home. My paternal grandfather, Eugene Hackford, who was a bookkeeper, purchased a newly built brick home in a new suburb of Buffalo (above right) for his wife and four children. My father believes they paid around $6,000 in the late 1930s (equivalent to about $126,000 today), when median annual income was about $723.