When my dad turned 80 a few years ago, I gave him a 23andMe genetic test for fun. His DNA report said he is 100% northern European, primarily from the Alsace region of Europe, an area along the Rhine River that has fluctuated between German and French control in the last 150 years. The results matched what we already knew about his ancestry from family lore—there were no surprises except for a small but significant percentage of DNA from the Netherlands.

For others, genetic testing can be full of surprises. One woman I know learned that the man she calls her father is not actually her father. After taking a DNA test, she discovered her biological father’s family and a number of half-siblings. When confronted with this information, her mother reluctantly admitted to a long-ago affair. Another acquaintance told me she knew she was adopted but not that she also has a number of siblings, which she discovered when she took a test. After the initial shock, these women now appreciate their new connections.

For a historian, the idea that we could possibly discover lost or unknown linkages between people and places through a simple test is exciting. We spend a lot of time trying to find tiny bits of information in vast archives, imagining the stories that might lie behind an artifact, and dealing with frustration at the limited documentary sources remaining or photographs that no one thought to label. Taking the guesswork out of our origins feels too good to be true. And, to some degree it is. Because there are other ramifications of the technology to consider.

Think about the people whose DNA helps to capture criminals who left their own DNA behind at a crime scene. Revelations about those kinds of shared origins could hardly be celebrated beyond appreciating that a criminal might have walked free if not for the test.

For Black Americans, DNA testing can be problematic. DNA tests like those used at 23andMe use reference groups—people alive today who share genetic sequences common to people of a certain area—to deliver results. A function of who is taking the tests, the reference groups are much more robust for people from North Atlantic European populations than for those from other parts of the world. For people of African descent, the reference groups are sparse. But, due to historic abuses by government and health officials, such as the notorious Tuskegee syphilis experiments, Black Americans may be reluctant to participate. This means that they won’t have access to the health data encoded in their DNA that could provide helpful—even potentially life-saving—information.

Further, receiving a DNA report that includes percentages of white DNA that might be the result of coercion or rape, could be difficult to deal with emotionally. Recently, two Stanford researchers developed a model to estimate the average number of genealogical ancestors from African and European source populations for a random African American individual born between 1960–1965. They discovered that, on average, there would be 314 African and 51 European ancestors. (Read the article here.)

It’s important to understand that all DNA information is probabilistic. That means that even if your DNA test says you are likely to have curly hair, you may not. While DNA revelations can still be exciting, perhaps we should think about what these tests seem to reveal with a deeper understanding of what they don’t.

History Today

“How Genetic Genealogy Helped Catch The Golden State Killer,” a Forbes article by JV Chamary, outlines the steps used to catch criminals with genealogical data as well as traditional geneaology research. Ex-policeman Joseph DeAngelo, who raped, murdered and burgled victims throughout California in the 1970s and ’80s, was finally caught in 2018 using DNA information from people who turned out to be his third cousins. Read the article, or see this more recent story in Slate that discusses how current privacy regulations could prevent investigations (and captures) like this.

What I’m Reading

I thoroughly enjoyed Last Call at the Imperial Hotel: The Reporters Who Took on a World at War (2023), by Deborah Cohen. The non-fiction book follows a handful of international journalists in the 1930s as they document the rise of Fascism in Europe, cheat on their wives and husbands with each other, and apply new Freudian theories to dictators, countries, and themselves. It made me nostalgic for a bygone time when pursuing the facts—no matter how difficult or unpopular—was a respected pursuit that the public appreciated. In the 1930s, books on international politics were bestsellers.

One takeaway: The book says that Freud developed his theory of the Oedipus Complex—where women purportedly have an unconscious desire for their fathers—when a large number of his female patients claimed to have been the victims of incest. Freud could not believe so many fathers could be so evil; he chose to assume the women were mistaken and that their reports were not statements of fact but rather unconscious urges. I’m still struggling to process this… !!!

Book News

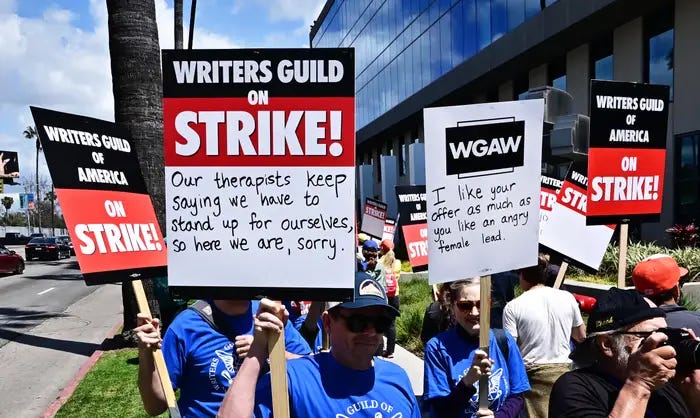

I don’t have any news to report about my book, so instead I will say that I support the ongoing Hollywood writers’ strike. My experience publishing and trying to market a book has made it clear to me that writing is a severely undervalued skill in our society. Those who provide us with hours and hours of entertainment should be compensated appropriately—and should not be threatened with the idea that generative AI chatbots can replace them.

I have played with ChatGPT in my day job at the Computer History Museum as well as edited my stepson’s ChatGPT-aided papers. I can say that while it is quite competent at synthesizing information into coherent, reasonably well-constructed sentences, it has zero insight and cannot say anything fresh or new.

Check out the human writers’ clever slogans on the signs above!

Origin Stories

My mother’s paternal great-great grandfather was Antoine Wind, and she was descended from his oldest son, John (1849-1937). Like my father’s family, they were also from Alsace-Lorraine. The Winds came from a little town called Ettendorf (see the blue arrow in the upper map) in what is now the Bas-Rhin region of France. While “Antoine” would suggest French heritage, he married a woman named Maria Schneider, a German name. John and his son Anthony (1879-1958), who both emigrated to the US in 1887, spoke German. An interesting note on the genealogy page above brackets John’s three younger siblings and reads: “Some went to Africa when Germany took over land.” I originally thought that they had left Alsace when Germany annexed the region in 1871, perhaps displeased with the change in rulers. But that would mean they had waited 16 years to leave, so I realized it made more sense to connect the family’s departure with Germany’s (brutal) colonization of Africa, which happened from 1884 to 1890. No doubt, I share DNA with people on that continent.

Thanks for reading Living With History! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.