Last week, in a lunchtime discussion on diversity, my colleagues and I talked about the gaps in our K-12 education. We realized that no one had ever heard of the Tulsa race massacre until recently. American slavery had been treated primarily as an economic issue. California state history was taught as a linear progression—first there were the Native Americans, then the Spanish, then the Mexicans, and then the gold rush. In my middle school New York State History class, we watched the 1977 movie The Last of the Mohicans, which literally portrays the end of a race. But Indigenous people are still here. They are not a closed chapter in the history books.

I was reminded about a case near my own hometown of Buffalo, New York. Grand Island (image above), and a series of smaller islands, sits in the middle of the Niagara River and was once home to the Seneca Nation. Everyone in the area is familiar with the Seneca Reservation—“the Res”—where you can buy tax-free cigarettes and gas. In 1993, the Senecas sued the State of New York to try to recover the islands. The basis of the suit rested on the 1792 Non-intercourse Act, a law that said you could not have a treaty and take land from an Indian without federal government approval. But that was exactly what New York State did in the Treaty of 1815.

I remember hearing that people who lived on the Island were upset that events from so long ago might disrupt their lives. Disbelief and anxiety mixed with confidence that the case would be dismissed. Worries about the case sent property values plummeting, and many of the historic old homes on the island were put up for sale. People asked where the limits were if the Senecas won the case. Would the US cease to exist if all such claims were honored?

Then the US Department of Justice joined the fray—against the landowners, noting that, "The Seneca Nation has an historical and federally protected interest in this land… New York State violated federal law when it purchased the land without Congressional approval in the early nineteenth century. It is time to right this wrong."

But, in a strange twist, this was apparently a maneuver to shield current landowners from liability. A representative of the Attorney General wrote, “At the outset, we agree that private landowners should not bear any potential liability in the Indian land claims in New York State. The private landowners purchased their land in good faith from New York or from earlier good faith purchasers and therefore should not be subject to Liability or bear any burden in defending these claims.”

The judge agreed with them. In 2002, Federal Judge Richard Arcara rejected the land claim for Grand Island filed by the Seneca Nation of Indians. He essentially said that Great Britain’s land grab passed on title to the new United States after the Revolution. If that wasn’t enough, even if that title could be rejected under the Non-Intercourse Act, then a 1784 Treaty effectively extinguished the Seneca’s claim. Here’s the legal jargon:

The Seneca Nation’s aboriginal title to the Niagara Islands, if in fact the Senecas ever held such title, was extinguished prior to New York’s purported purchase of the Islands in 1815. In 1764, pursuant to treaty, Great Britain extinguished any claim of Seneca title to the Islands, thereby securing fee simple absolute title to the Islands for itself. Upon the American Revolution. Britain’s fee simple absolute title passed to the State of New York. Furthermore, pursuant to the 1784 Treaty of Fort Stanwix, the United States again extinguished any claim of title the Senecas may have had to the Niagara Islands. Under the Articles of Confederation and the law of Indian land tenure, once the Senecas’ title was extinguished, New York, as the holder of the right of preemption, obtained fee simple absolute title to the Islands (assuming of course that New York did not already possess such title as a result of the 1764 treaties).

There is some evidence that the Seneca chiefs who signed the 1784 treaty were hostages. But no one in the Grand Island case seemed to care about exploring the implications of that for their descendants’ land claims.

Similar Indigenous land claims in other states have been resolved through negotiation and the states and federal government have reached agreements that compensated tribes and eliminated questions about the land title of present-day owners.

I’m sorry my hometown didn’t do better for our Seneca neighbors.

Sources

http://isledegrande.com/senecainfo.htm

https://www.justice.gov/archive/opa/pr/1998/March/129.htm.html

https://www.thehypemagazine.com/2018/01/seneca-evidence-doesnt-add-up/

History Today

“Googling for oldest structure in the Americas leads to heaps of debate.” This August 28, 2023, Washington Post story by Jordan P. Hickey explores the claim that earthen mounds on the campus of Louisiana State University in Baton Rouge are the oldest known human-made earthworks in the Americas—up to 11,300 years old. The article focuses on how Google’s algorithms and a bias toward superlatives leave out the many archeologists who disagree. But it also talks about how settlers refused to believe that such mounds—found in various parts of the country—could have been constructed by the ancestors of the Indigenous people who they were busily decimating. Instead, they preferred to believe in a mythical “extinct race.” Read the article.

What I’m Reading

This one is on the top of my to-read list. The Hidden Roots of White Supremacy: And the Path to a Shared American Future (2023), by Robert P. Jones, explores three cities that experienced racial atrocities against Black and Indigenous people. Reading a review inspired me to use it as the basis for my lunchtime discussion at work.

Jones grew up in Mississippi, only nine miles from Medgar Evars’ house, but no one ever talked about the civil rights leader in his family or in school. He didn’t know that the word “Southern” in the name of his Baptist church meant that the Baptists had allied themselves with slaveholders who sought to justify the practice in scripture. As a student at Mississippi College, he never learned about the genocide and forced removal of that tribe and others from the land on which it sat.

Book News

My aunt recently asked the manager at her new home in South Carolina to include my book in the clubhouse library. (Thank you, Aunt Gay!) The woman immediately recognized the house on the cover as Drayton Hall, an historic home in Charleston. Just like the fictional Folly Park, it is now a house museum. Check it out if you’re in the area!

Origin Stories

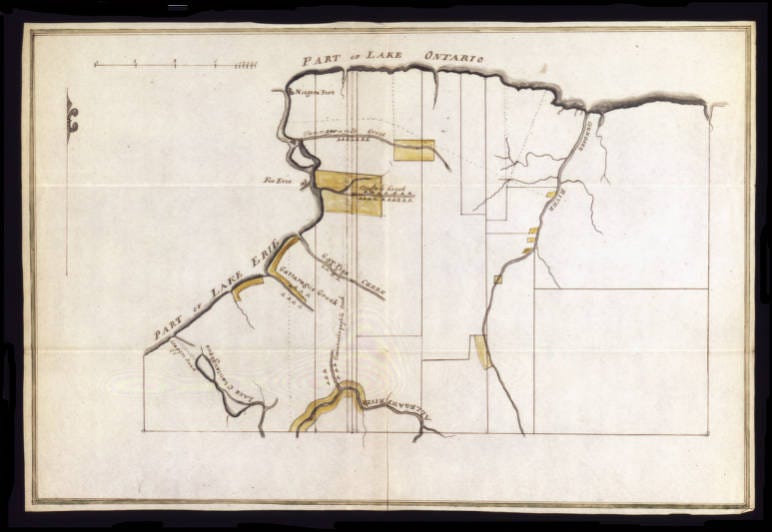

Map of the West Genesee Lands with Indian territories; 1797. This map shows Indigenous settlements in Western New York, including the site of the future city of Buffalo. (You can blow up the map here to see the triangles that represent the settlements; also, note Lake Chautaughqua in the lower left, where my relatives have a summer place.) The city, and the suburb of East Amherst, where I grew up, used to belong to the Seneca. In 1798, the Holland Land Company acquired most of the land and sent Joseph Ellicott to survey it.

Ellicott also expanded narrow Indian trails into the roads that my family would frequently drive on 200 years later. The Great Iroquois Trail, which crossed the state from Albany to Lake Erie, became the Buffalo Road and then Main Street. Ellicott hired White Chief (also called White Seneca) to make a straighter trail on higher ground that extended from south of Orchard Park—the next town over to my parents’ and sister’s current homes—to Lake Ontario. Transit Road, with which my childhood street intersected, was named for the instrument surveyors used to straighten it. White Chief was paid $10, equivalent to about $244 today. Learn more.

Thanks for reading Living With History! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.