Vanished Communities

Finding Black people and places in history

Recently, I learned that there used to be a thriving 19th century village just a couple of miles down the road. There’s nothing left of Purissima now but a cemetery and a cypress grove. When the railroad left, the town died.

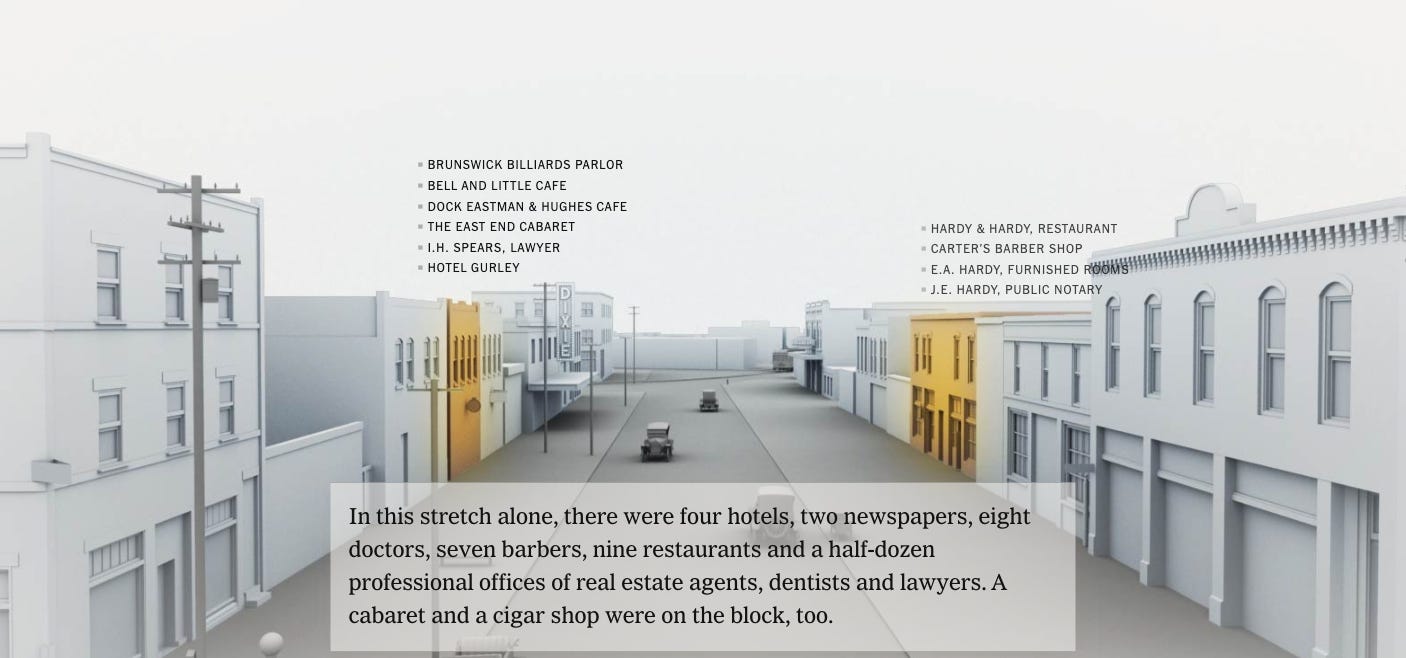

Reading about this “lost” village reminded me of the vanished Vinegar Hill, near where I lived in Charlottesville, Virginia (see image above). Vinegar Hill was a thriving Black community razed in 1965. The city’s largest Black neighborhood and a hub of social life, 139 homes and 30 Black-owned businesses and a church were destroyed in the name of “urban renewal.” The land was valuable, and the city was eager to redevelop it into shops and apartments . . . for White people.

This kind of destruction was the rule more than the exception in the rapidly growing post-WWII United States. In the last few years, some cities have explored efforts to compensate residents and their descendants for property taken by eminent domain for public projects (read more). In my hometown of Buffalo, NY, I often traveled on the Kensington Expressway, passing large and stately homes butting up to the traffic. Recently called a “mistake” by NY’s former governor, the road destroyed the thriving Black communities around Humboldt Parkway—part of the beautiful park system designed for the city by Frederick Law Olmstead.

Of course, Black communities were also lost through violence and destruction. Suppressed in the papers of the time but later referred to as a “race riot,” what happened in Oklahoma 100 years ago has been more accurately renamed “the Tulsa race massacre.” Following an incident between a White woman and young Black man in an elevator (it is believed he may have stepped on her shoe), White vigilantes burned more than 1,200 homes and killed hundreds. Claiming they feared that word of the young man’s arrest would draw unruly Blacks from the surrounding country and nearby neighborhoods, they preemptively annihilated what was known as “the Black Wall Street.”

The narrative used in Tulsa was honed during slavery. In Tumult and Silence at Second Creek (1995), historian Winthrop D. Jordan, explores a slave conspiracy in Mississippi in 1861. Hearing of the outbreak of the Civil War, a number of slaves in a wealthy, established plantation community allegedly plotted to kill their masters and take the White women. Fearing the unrest would spread, dozens of slaves were questioned and summarily executed by an extra-legal “Examination Committee” of slave owners. These slaveowners gave up their legal right to be compensated for their executed slaves in the name of secrecy, fearing that it might inspire other uprisings or provide ammunition to the Northern cause. One woman wrote to her niece:

“It is kept very still, not to be in the papers . . . don’t speak of it only cautiously.”

Although the houses where the Second Creek slaves lived have long disappeared, many of the mansions still stand. Some are tourist attractions.

***To see what communities have been lost in your hometown, google “urban renewal Black neighborhoods [YOUR CITY].”

History Today

After nearly two centuries of legal and illegal destruction of their homes, businesses, and even their lives, perhaps the greatest threat to Black communities today may be the changing climate. Like Princeville, North Carolina, long-standing Black towns were often built on the least desirable land, which today is subject to drought, floods, hurricanes, and the accompanying scourges of disease and pollution. Had Black communities been permitted to thrive, they likely would have provided generational accumulation of wealth similar to White communities—a buffer against change.

What I’m Reading

Pulitzer Prize-winning author Marianne Wiggins’ latest novel, Properties of Thirst (2022), was completed after she suffered a debilitating stroke halfway through writing, and it’s a page-turner. Set in California during World War II, it focuses on Rockwell “Rocky” Rhodes’ on-going battle with the Los Angeles Water Corporation, which dried up a nearby lake and destroyed farms and ranches to slake the thirst of the growing city. Meanwhile, the US government determines that the area—Manzanar—is the ideal place to build a relocation camp for American citizens of Japanese descent imprisoned during the war.

Book News

I have finally turned in the finalized manuscript to be sent to the printer! Whew! I’m now turning my attention back to marketing efforts (sooo much fun—ugh). I’ve put together gift bags for local bookstores with advance reader copies to see if they will consider stocking Folly Park. Shelf space is at a premium and the competition is heavy. I’m hoping the “local author” plea and sea salt caramels will give me an edge!

Origin Stories

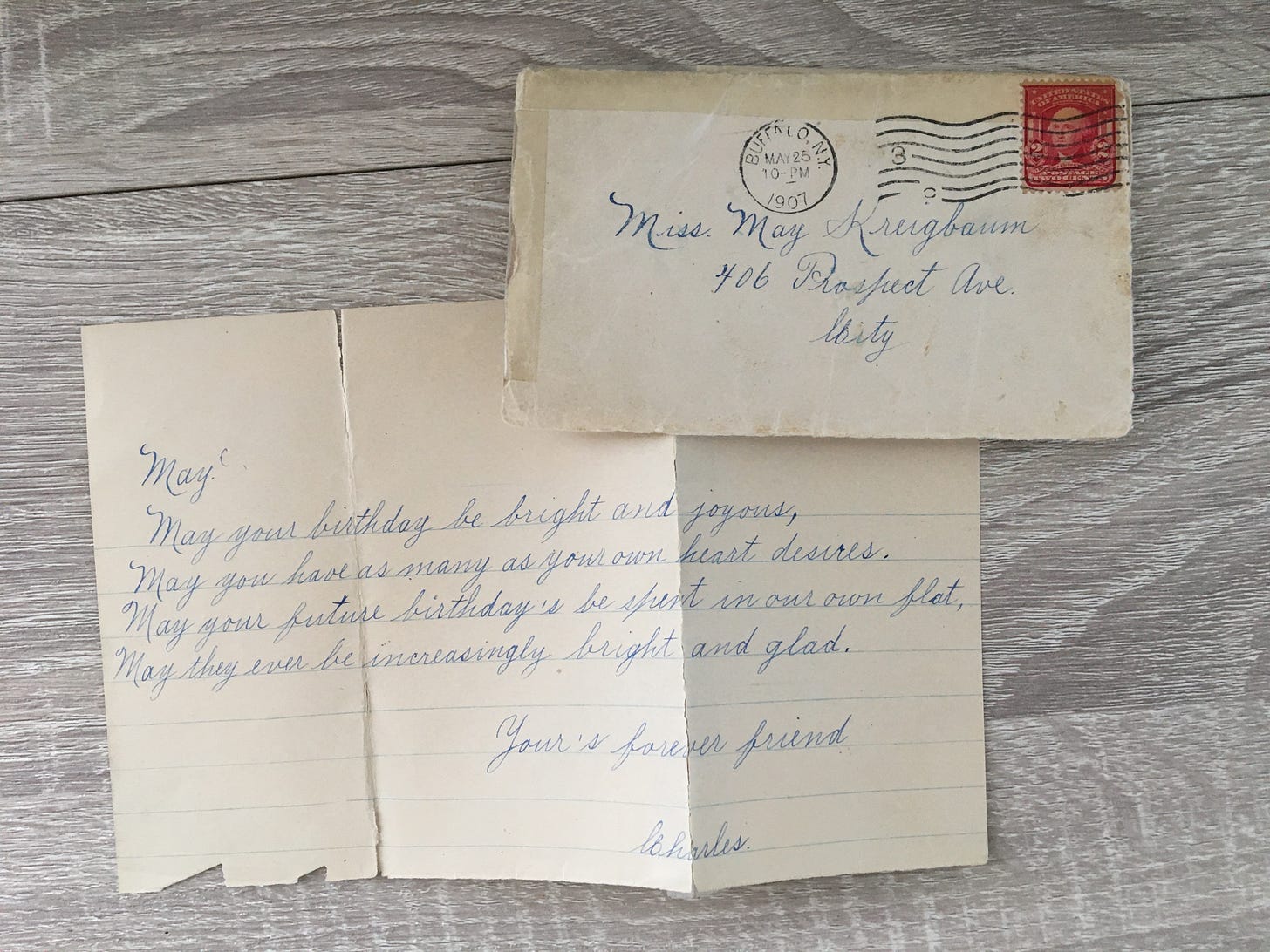

Charles Hereth to Mary Kreigbaum Hereth (May 25, 1907). My paternal great grandfather wrote this note to my great grandmother on her birthday while they were engaged. He writes, “May your future birthdays be spent in our own flat…” When they married, they did indeed have an apartment in downtown Buffalo. In fact, both my mother and father had grandparents who lived on the same street—Herman Street—in the “German section” of the city. In the next generation, their children would start married life in city flats and then move out to the suburbs, where my parents grew up. With this “white flight,” the neighborhood became predominantly Black. Herman Street intersects with the Kensington Expressway pictured above.

Thanks for reading Living With History! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.