Visiting my parents recently, I came across an envelope with a few documents and photos related to my father’s family history. Someone had done some genealogical research. There was a family tree that went back five generations, and I discovered a bit of a mystery.

The entry for my dad’s paternal great-grandfather read: “?? HACKFORD (HACKAFORT).” The first name was missing and there was apparently some confusion about his last name. Next to him was the name of his wife, Rosa Hund, and the chilling note: “Fell out of tree.” Rosa had apparently died at the age of twenty-five, leaving a two-year-old-son named John (my father’s grandfather). The boy was noted as living with his Hund grandparents in 1880 when he was four years old, that fact perhaps gleaned from a census record. This suggested to me that John’s father had left him to be raised by his dead wife’s parents and had moved on, perhaps never to return since his first name had been forgotten. The child, John, carried the last name “Hackford” forward, however.

I had been told the family Anglicized the name from “Hackfort” to “Hackford” during World War I, when German-Americans were eager to dissociate themselves from a country with which the US was at war, but the genealogy suggested that perhaps the name may have been changed earlier. Did someone remember that the mystery father had once said his last name had been changed? Or, did the family researcher discover that the name had once been Hackafort, and if so, why hadn’t that person been able to also discover the missing first name. It’s a frustrating puzzle.

Our names are fundamental to our identity. From the time we’re born until we die, our names tell us where we belong in the world and are a crucial factor in determining our sense of self. As anyone researching history will tell you, a missing name is more than just a gap in the record—it is a mystery to be solved, a hole of possibility that encompasses all things until we can fill it with information.

Women’s first names and maiden names can be lost to history since often the sole record of their existence is a cemetery headstone identifying them only as “wife of”. The journal of 18th century mid-wife Martha Ballard, for example, is extremely unusual in that she not only kept a journal but also that she recorded her full name. Enslaved people were often not permitted to retain their birth names and may have been given new surnames or even first names when they were sold—making tracing ancestry very difficult. Similarly, when immigrants could not make themselves understood by immigration officers, those officials recorded what they thought they heard. That also happened when settlers encountered Native-American names. Who knows how far removed they are from the originals?

We are a country of immigrants, and we may find unfamiliar names difficult to pronounce or to remember. In my late twenties, I discovered with horror that I had been pronouncing a good friend’s name wrong since I met him the first week of college. Many immigrants change or shorten their names so that they more closely resemble typical American names—losing some part of themselves to make it easy for the rest of us.

Please, let’s make a sincere effort to learn people’s true given names and how to pronounce them properly. It might remind us all that we’re not strangers but fellow travelers on the same human journey.

History Today

Many African American Last Names Hold Weight of Black History

This NBC News article by Julia Craven explores how the legacy of slavery has complicated the names of Black Americans . The complexities make it difficult for many to accurately trace their genealogy, although DNA testing may help if more people are willing to submit samples. It is NOT true that most freed slaves took on the names of their former masters. Such a narrative literally whitewashes the fact that slavery was a brutal, dehumanizing institution and, given a choice, few of its victims would voluntarily take on the names of their oppressors. Read the article.

What I’m Reading

The Indigo Girl is a very well-written and researched historical fiction novel by Natasha Boyd. It is based on the life of Eliza Lucas Pinckney, who is credited with being the first colonial planter to experiment with and raise indigo successfully as a cash crop; indigo dye made up one third of South Carolina’s exports before the Revolutionary War. Boyd sets the record straight by focusing on how Lucas learned the complicated production process from enslaved people, who had experience making indigo in the West Indies and in Africa.

Book News

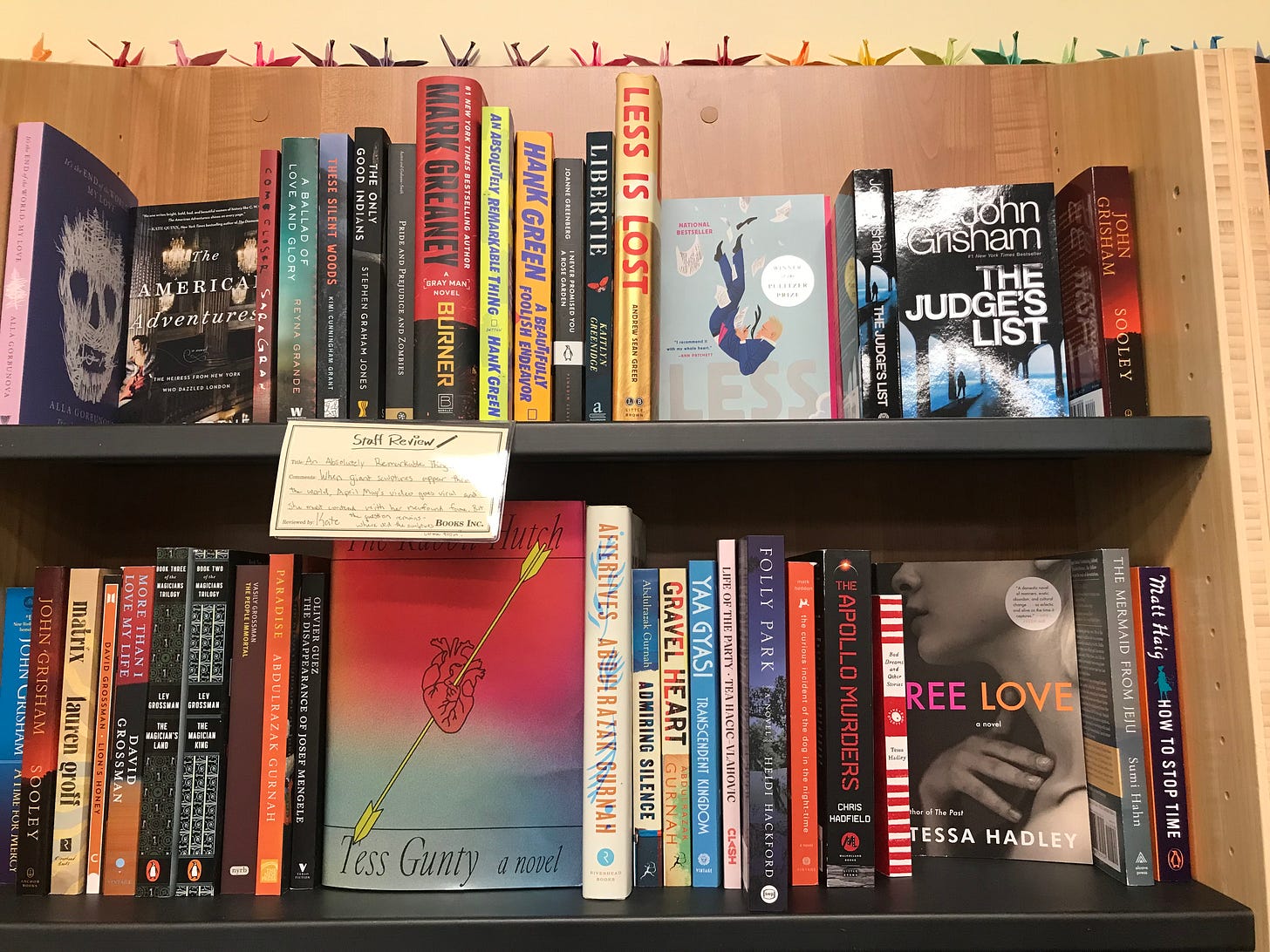

The owner of my local independent bookstore, Coastside Books in Half Moon Bay, was apparently inspired by my novel to set up a section of her limited shelf space specifically for historical fiction, which is where my husband purchased The Indigo Girl for me. Can you find my book, Folly Park? It’s in great company!

If you haven’t gotten around to reading Folly Park yet and would like to, you can purchase a copy from this independent online bookstore or on Amazon.

Origin Stories

John Hackford, second from left, and his wife Adelaide “Lil” Mackenberg Hackford (c. 1900?). This photo was taken on the occasion of the wedding of Lil’s sister, Clara, (seated). My father’s paternal grandfather looks exactly like photos of his son, Eugene, my paternal grandfather. By all accounts, they were both very kind men. I wonder if they looked like John’s nameless father, and if he too was a very kind man. For me, that makes his personal tragedy and the fact that we do not know his first name even more poignant.

Love the photo of the family!

My husband's ancestors changed their names a few times due to anti-semitism here. His grandfather eventually was able to become a professor, with the bland last name of Brown.