On a recent trip to Oregon, my husband and I stopped in Lakeport, a charming 19th century town that looks like it has been frozen in time since the1950s. It was a sunny Saturday morning, and there was a vintage Volkswagen car show going on in the public park that lines the shore of Clear Lake. We had lunch with a view of people boating and fishing and talked about Eric’s family ties to the area, including his mother learning to waterski on that very same lake in the 1950s.

Unfortunately, it’s not a good idea to swim in the lake or eat the fish caught in it. Belying its name, cinnabar mining throughout the area in the previous century has left Clear Lake poisoned with mercury.

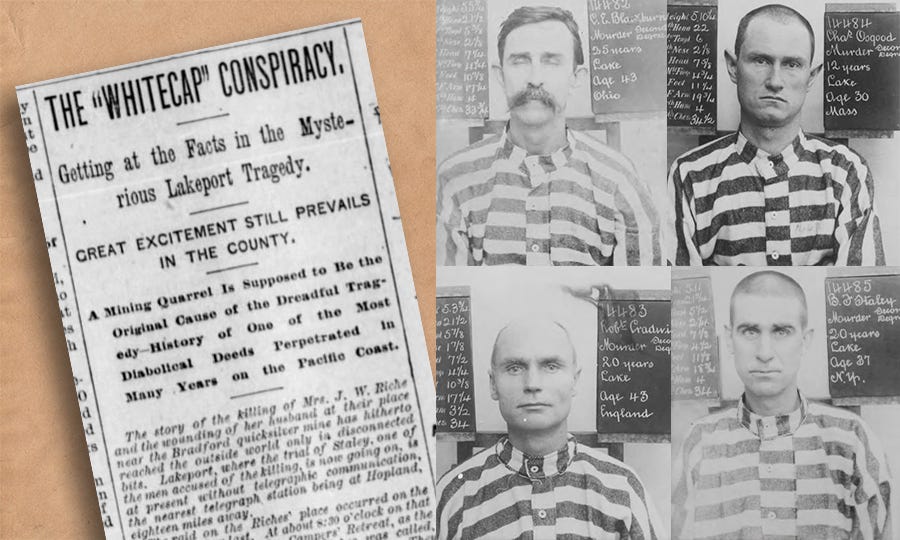

Being the nerdy historians we are, we paid a visit to the local historical museum located in the restored courthouse. The plaque outside the building noted that the courthouse was the site of the trial for the infamous “White Cap Murders” in nearby Middletown that shocked the country in 1890. We had never heard of them.

On further exploration, we learned that nearly a dozen men, dressed in the white hoods favored by lawless groups in the 19th century, had taken advantage of a local candidate’s ball one October night to storm what was usually the crowded Campers Retreat saloon. They shot and killed the proprietress, Mrs. Riche, fatally injured her husband, and nearly killed employee Fred Bennett, their true target, who they had planned to tar and feather and run out of town.

Apparently, many of the men—miners at the nearby quicksilver mines—held a grudge against Bennett for his treatment of them at the saloon. Later investigations showed that a wealthy mine owner with competing interests with Bennett had perhaps whipped them up to do the deed. He himself remained unpunished while four men were sent to San Quentin prison.

The violence was considered extreme, even for an area with a Wild West mentality, and we wondered if the fact that the men were mining quicksilver—or mercury—could have contributed to their actions. Mercury is a neurotoxin, and long-term exposure can lead to, among other symptoms, mood swings, irritability memory problems, difficulty concentrating and, in extreme cases, psychosis or hallucinations.

Learning more about the history of the lands where we live, work, and play is an urgent imperative today, a time when we’re finding toxic microplastics in the snow on Everest, in the depths of the oceans, and in our own bodies. Fertilizers and pesticides have been linked to neurological disorders like autism and Parkinson’s disease. I shudder to see children playing in the creek that empties onto our local beach, creating a little pond. The creek passes through farmland, gathering toxins on its way to the ocean.

We all might benefit from being a bit more curious.

Sources

There’s plenty to find on the internet about the White Cap Murders, but I found this document, to be the most well-researched and thorough.

History In the News

California Zombie Lake Turned Farmland to Water appeared in The Guardian a couple of months ago. It reports on the status of Tulare Lake, which reappeared more than a century after it had first been drained for farming. Heavy rains filled the lake again in 2023, drowning infrastructure, homes, and trees, and bringing back fish, migrating birds, and awed tourists. It’s mostly dried up now but likely to come back again as climate change brings more extreme droughts and more extreme storms. Read the full article.

(It might be good to know that your house is sitting on a dry lake bed!)

What I’m Reading

The 200th anniversary of Lewis and Clark’s journey occurred in 2004, when I was working at Monticello. Jefferson had conceived of and authorized the Corps of Discovery expedition, and we were allowed to attend the local lectures and events involved. At that time and previously, I had always seen the trip conveyed as a dangerous trek through raw wilderness, and the explorers sent remarkable samples of unknown plant and animal species back to Jefferson. But the land wasn’t a “wilderness” from others’ perspectives.

Lewis and Clark Through Indian Eyes (2006), edited by Indian scholar Alvin M. Josephy, Jr., includes nine essays from Indian writers who set the record straight. You can almost feel their eyes rolling as they report that the land through which Lewis and Clark traveled was inhabited by heavily populated Indian nations who had long-established relationships with European traders and sailors. To them, the Corps was just another (unremarkable) group of white men passing through.

Origin Stories

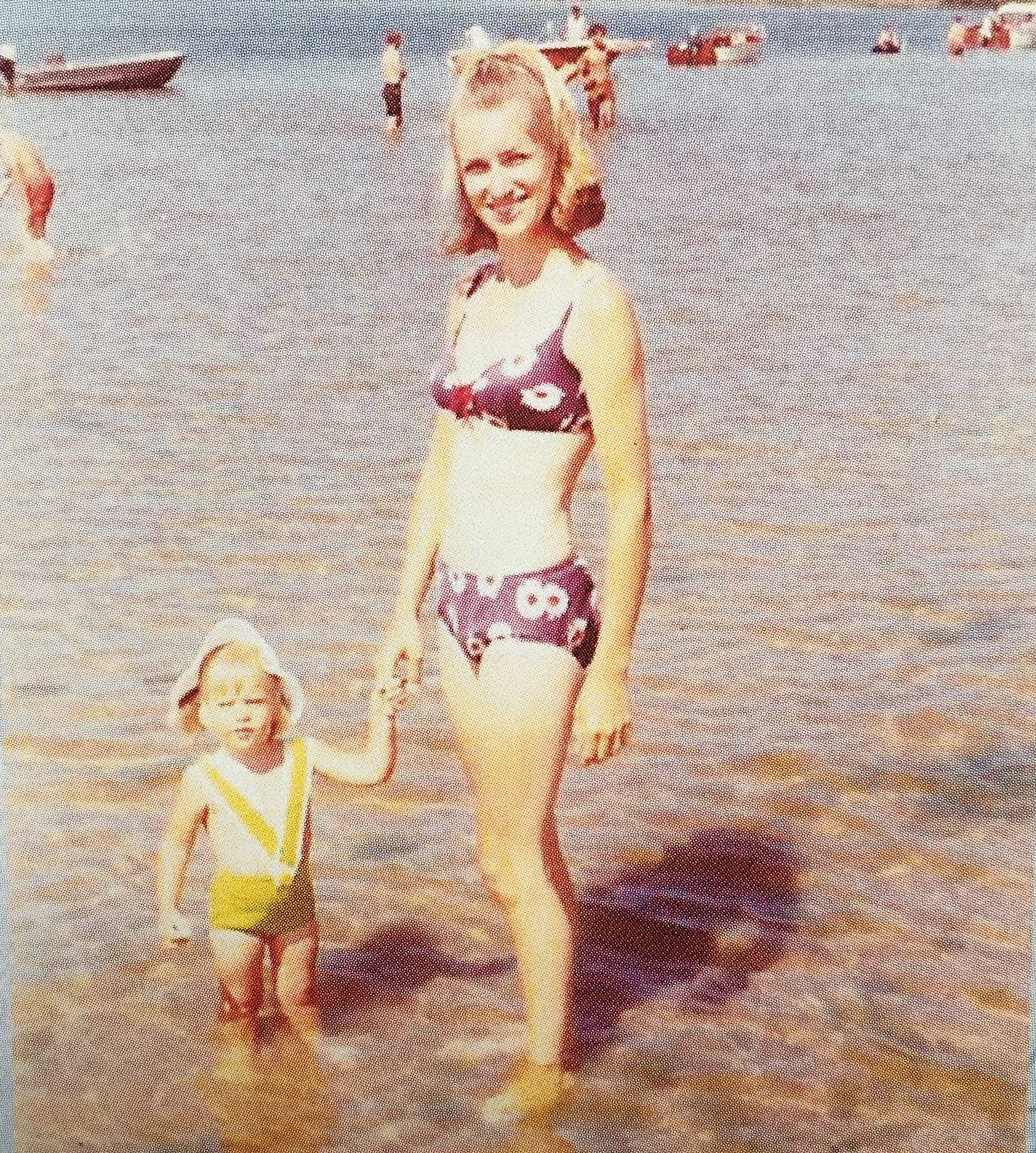

Me and my mom, Bonnie Wind Hackford at Lake Erie (1969). Generations of my family have spent time on the shores of Lake Erie since the early 20th century. By the 1960s, it was so polluted from industrial waste and sewage that parts of it were declared dead. In 1969—the same year as the photo above—the Cuyahoga River that drains into the lake caught on fire, leading to water quality agreements signed by both the US and Canada.

In the 1980s, my family enjoyed summers at my aunt and uncle’s cottage in Canada. A couple of times a month, a nearby farmer opened the drainage ditch that ran along the road and sent farm (and cow manure) runoff into the lake. It spread along our beach, turning the water to the color of iced tea for a few days. We waded through the polluted—and likely toxic—water to swim.

Thanks for reading Living With History! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.